Soundtracking the Age of Monsters

Film music budgets are already at historic lows, and AI is by some claiming to be the final nail in the coffin for commissioned art. But that’s just a market fever dream—Exhibit A is the fourth wave of film music that rumbles on the horizon. As Gramsci wrote from the fascists’ prison: “The old world is dying, the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.”

The Solitary Craftsman

By the late 1960s it had become both financially and technically viable for music creators to build personal professional studios. The solitary music producer emerged as a new kind of film worker—able to deliver high-quality commissioned music by increasingly acting as both sound engineer and recording technician. A growing demand from the film and television industries meant that more of these niche creators could make a living from music without ever setting foot on a stage. Or dealing with musicians.

The solitude suited certain artistic temperaments perfectly, and they rewarded us with masterpieces that methodically explored and expanded music’s technical and artistic boundaries. Smaller budgets produced new creative solutions. Generous studio budgets, on the other hand, enabled longer and more intense work on film scores than ever before. Music became central to the art of film.

The greatest master of them all, Ennio Morricone, brought in his improvisation group to score the sequences in Un Tranquillo Posto di Campagna that depict the protagonist’s descent into madness. The film itself wasn’t a major hit, but showed that radical modernist music could thrive in a commercial narrative film—so long as it was composed with feeling. Unlike many composers of his time, Morricone adored The Movies, and his combination of classical training from the Santa Cecilia Conservatory and deep involvement in experimental sound art made him truly singular. Many took notes.

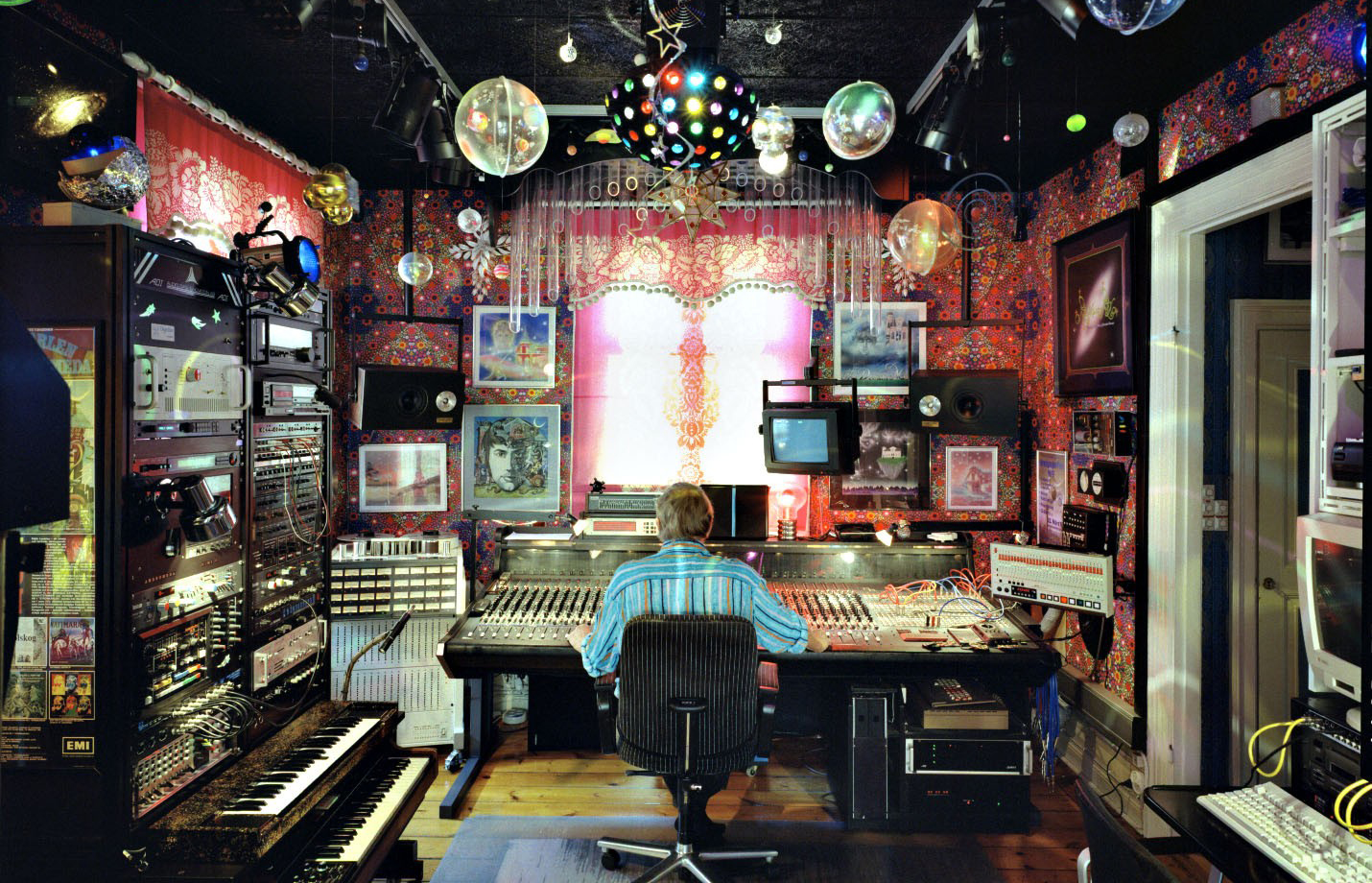

Demand for music’s solitary creators grew throughout the seventies and eighties as composers like Artemyev, Carpenter, and Moroder developed and crafted extraordinary musical worlds with very few—or no—musicians besides themselves. They still had ample physical space, though: accounts of how the Blade Runner soundtrack was created make clear, for example, that Vangelis’s London studio Nemo was the size of a Stockholm 4-bed apartment with six-meter ceilings. As samplers and synths became cheaper and more efficient, however, the need for musicians shrank—and so did the need for floor space. By the early nineties, entire scores were created in tiny rooms. Film composers who wanted to work alone now could.

Solo Creation in 2-channel Sweden

Sweden’s biggest names in film music continued working with ensembles and orchestras of varying sizes, but solo composers started to create remarkable scores for low-budget films and documentaries here as well. Those on the same artistic wavelength as their international peers mostly had to settle for idents, experimental films, installations, and art television though. The few who got to work for Swedish public service television got the children’s programs, regional shows, and dance films. From this era, the nature-film scores by Swedish electronic-music pioneer Ralph Lundsten are worth exploring, as are the sound experiments of Åke Hodell and the still active electroacoustic composer Ragnar Grippe.

Big copyright money from solo project-copyrights were rare: creators were paid fixed fees like other film workers. The recordings that reached a broad audience outside cinema took an Astrid Lindgren-story-based movie and live ensemble-music to justify a release. Solo composers without parallel artist careers had one way to secure an income in 2-channel Sweden: work in volume and imitate expensive-sounding music at the lowest possible cost.

Slim budgets forced Swedish solo creators into new forms of creativity that sometimes led to exciting art. However, over time, they were pushed further and further away from the core of filmmaking. With the few higher budget productions of the seventies and eighties, directors worked as closely with composers as cinematographers and editors. This proximity created huge artistic potential but also cost-efficiency, as story changes could quickly be met with new music. The musicians couldn’t be kept on standby, of course, but composers with strong reputations were central for assembling whatever was needed to reach the desired quality fast. The solo creators didn’t have that problem, and accepted lower fees and evolving sound quality that the audience accepted. The price: loss of relevance.

Commissioned Music 2.0

In the nineties, conditions changed dramatically for Sweden’s solo creators due to a unique set of factors: first of all, the dismantling of the state media monopoly led production companies to compete ever more aggressively with ad-inflated budgets. Simultaneously, Swedish pop music export soared and new digital recording technology made it possible for own studio-owners themselves to justify scoring everything, both cheaper and more. Music began to take up space again in the freshly deregulated production landscape. Swedish music and advertising soon paved the way for those seeking international work. The commission budgets followed and for a few years there was serious money to be made for solo creators.

A few years later, as file-sharing spread and the bottom fell out of the recording industry, commissioned music became even more normalized. Selling songs or composing for commercials became kosher as fewer critics shouted “sellout” and the entire music industry was pressured into concessions. When José González’s cover of The Knife’s Heartbeats scored a global Sony Bravia campaign, it gave him significant momentum toward an international breakthrough.

The market’s siren call allowed capital to reclaim its grip on music. It had no intention of letting go.

Cheap music became so good that it took a genuine musical interest to distinguish trash from art—giving production-company owners exactly the arguments they needed to cut music budgets. Artistic ambitions dropped as directors began buying cloned music to meet budget demands. The market still hasn’t recovered. Solo creators met expectations by adapting in order to survive. In the new digital world—where tailor-made content for each individual user seems to be the platforms’ only lever for increasing revenue—film music was forced from differentiation to price competition. Once economists stopped sharing the wheel with creatives, Sweden would—as usual—go further than most countries. The film scoring business model was completely broken by home-grown entrepreneurs who had identified an opportunity on the market. To make commercials and TV shows sellable globally without slow, costly rights negotiations for each new market, soulless royalty-free music became the norm.

Production companies got rich with advertising money and had learned just how expensive music rights could become when a project unexpectedly succeeded abroad. When they started making film and TV, they applied the same principles. By demanding copyrights even for artistically ambitious projects, which could come to mean income for decades, they devalued film music—and themselves. Short-term profit interests turned many composers into subcontractors rather than artistic co-creators. To stay competitive in a market driven entirely by quantity, composers became the anonymous assembly-line workers they still are today.

The catalogues go online

In 2009, one year after Spotify’s broad launch, the economist Oscar Höglund founded a platform for royalty free music—Epidemic Sound—together with a few musicians and venture capitalists. He had seen how production companies struggled with music and had a business idea perfectly attuned to the moment. Like Spotify, the company benefited enormously from the global financial crisis, which really became the lucky break for both companies. It’s easy to forget—since the winners gets to write the history—but the two Swedish music-tech unicorns were built on exactly the same business principles as IKEA and H&M. By marketing themselves with precision to the most price-sensitive users, they could make cost-efficient distribution the core profit driver instead of quality.

As Epidemic intensified competition, the market for commissioned music was disrupted a third time. New companies popped up and began price competing by creating their own factories and distributing commissions across huge stables of composers who had to accept vulture-like demands to sell off all or part of their copyrights to get the gigs. Conditions worsened for those wishing to make a living from music. And with virtually no collective representation—solo creators and studio owners are, after all, competing small businesses—the era that followed can be summed up in three words: total price dump.

.jpeg.webp)

Turning the volume to eleven

Cheap, powerful computers and top quality music-production software, combined with streaming platforms, YouTube, and social media, created a new reality for background music and commissions alike. Music creators, who in the nineties could earn a living by skillfully imitating existing music, were completely replaced and doesn’t make a cent from musical cloning. In the eternal chicken-and-egg debate about market forces, blame is always shared, but things might have looked very different if Swedish creators had held on to their bargaining power. That’s the problem with the technology for perfect imitation in art: there is no way to ”prove” quality is suffering. But it is.

The solo music creators who survive are the ones who invent new business models. Just like illustrators or photographers, they spend periods without assignments building portfolio. But to make ends meet they need to sell music for direct download from various platforms, where they compete with thousands of young creators who never knew art to be worth more than, say, 59 dollars. Bulk became a lifeline many cling to—but these models exist in a fractured, unsustainable market.

File-sharing, streaming, catalogue music—and now AI. Film composers have always had very little time to develop their own artistic identities; they where the Swiss Army knives of music and delivered to brief. But the rising competition created a race to the bottom driven by profiteering instead of reinvestment which made a beautiful artform into yet another content business. Those who competed through sound quality and hoped for regulation of AI somehow now find themselves in a dead-end street, alongside hordes of creators from every other field.

The fourth wave

Static business models lose out in the process economists call creative destruction—an idea more than thirty years old, honored with this year’s Nobel Prize in Economics, and central to late capitalism’s growth engine. But for music of artistic merit, the destruction has unwanted side effects. When music creators have to negotiate their own deals instead of a manager or label they tend to sell themselves short. Stiff competition always benefits entrepreneurs over creators. Across fifty years, three waves of technological and economic disruption took down the previous order, but the solo creators of film music failed to create stability. Their hearts beat for autonomy, for art. The result is a market where the innovations have become more effective than the innovators.

In film, ambition, demand, and desperation existed in a combination irresistible to finance. Some entrepreneurs who spotted the trends early managed to capitalize—while music creators are back at square one.

When creative destruction has run its course and the market shifts shape once again, demand for artistic depth and human authenticity will rise. We then enter a new phase, where differentiation is the only viable strategy for anyone trying to survive a market that is price-competing itself to death.

Now, when the contours of the fourth wave of film music are beginning to appear on the horizon, it will be the real artists who understand how to ride it. Let’s hope it lasts. ◾

Twelve international and three Swedish pre-1990 solo masterpieces

- EMS Nr. 1 – Ralph Lundsten (1966) [youtube]

- A Quiet Place in the Country (Un Tranquillo Posto di Campagna) –

Ennio Morricone (1968) [bandcamp] - A Clockwork Orange – Wendy (då Walter) Carlos (1971) [soundcloud]

- Solaris – Eduard Artemyev (1972) [youtube]

- Aguirre – Guds vrede (Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes) – Florian Fricke (1972) [spotify]

- Halloween – John Carpenter (1978) [spotify]

- Midnight Express – Giorgio Moroder (1978) [spotify]

- Theme for Jönssonligan – Ragnar Grippe (1981) [youtube]

- Blade Runner – Vangelis (1982) [spotify]

- Målaren – Ulf Dageby (1982) [spotify]

- Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence – Ryûichi Sakamoto (1983) [spotify]

- Terminator – Brad Fiedel (1984) [spotify]

- Fletch – Harald Faltermeyer (1985) [spotify]

- Manhunter – Michel Rubini (1986) [spotify]

- Kamikaze – Edgar Froese (1989) [spotify]