"Let Them Eat Likes"

In the middle of the diabolic era of content acid reflux, we need to remind ourselves why the very word is so useful to everyone who wants to reduce or preferably eliminate the value of art.

When music, images, film, and all kinds of texts became “content,” creators and cultural organizations should have drawn a line in the sand. But no one with a platform explained that works of art—whatever their quality—have content; they aren’t content. It’s been three decades since Bill Gates broadly (and perhaps willfully) misinterpreted the 90s essay Content is King—in which he groggily concluded that technology is, in fact, a means, not an end. Since then, most of humanity’s creativity has been commoditized for the neoliberal digital machines to devour. But those machines overlooked AI’s most important side effect: pop finally ate itself. We are now entering the era of content acid reflux.

n 2014 I wrote an angry essay about how the supposedly harmless word contenthad been accepted as the new standard in the Swedish media industry—in English, not innehåll, as we are always eager to display our Anglo-centrism—after Sveriges Uppdragspublicister (basically, Sweden’s Association of Publishing Agencies) rebranded as the silly “Swedish Content Agencies,” further devaluing creative work. Things have only worsened since. According to the consultants, it’s “creative content that keeps customers engaged,” not quality or price. I tried to summarize the industry’s self-destructive logic:

“The whole business model resembles those CDs of Beatles or Elvis covers you used to find at gas stations, where studio musicians were paid by the hour to imitate groundbreaking artists and funnel more cash to some unscrupulous third-rate music industry mogul.”

Readers mostly shrugged—clearly I hadn’t nailed the wording. But my inner Don Quixote was awoken with a cymbal crash last summer, when Swedish billionaire and Spotify founder Daniel Ek declared: “The cost of creating content today is close to zero.” In Ek’s eyes, imitating music had always required at least some human craft to fool the most inattentive listeners—and that craft still cost him money. When AI came along, allowing anyone with a computer to bypass the actual making of music entirely, his dreams could come true. Spotify could multiply volume a thousandfold. Good times? Not for creators. And not for listeners.

Let me try again:

The word content signals that value belongs to the outer container.

“What’s in this kombucha?” we might ask, reading the label—but what we pay for is still the bottle, not the tea, sugar, or kombucha fungus. The company that packages the contents is rewarded. That’s why it’s so corrosive to call songs content: the intent is to reduce them to commodities, with the implication that the packager and distributor—Spotify in this case—harvest the value.

But the divorce from the global tech giants that carelessly seized culture’s distribution infrastructure has begun, since computer art will always lose out to human-made art. The question is: why did we have to take this detour?

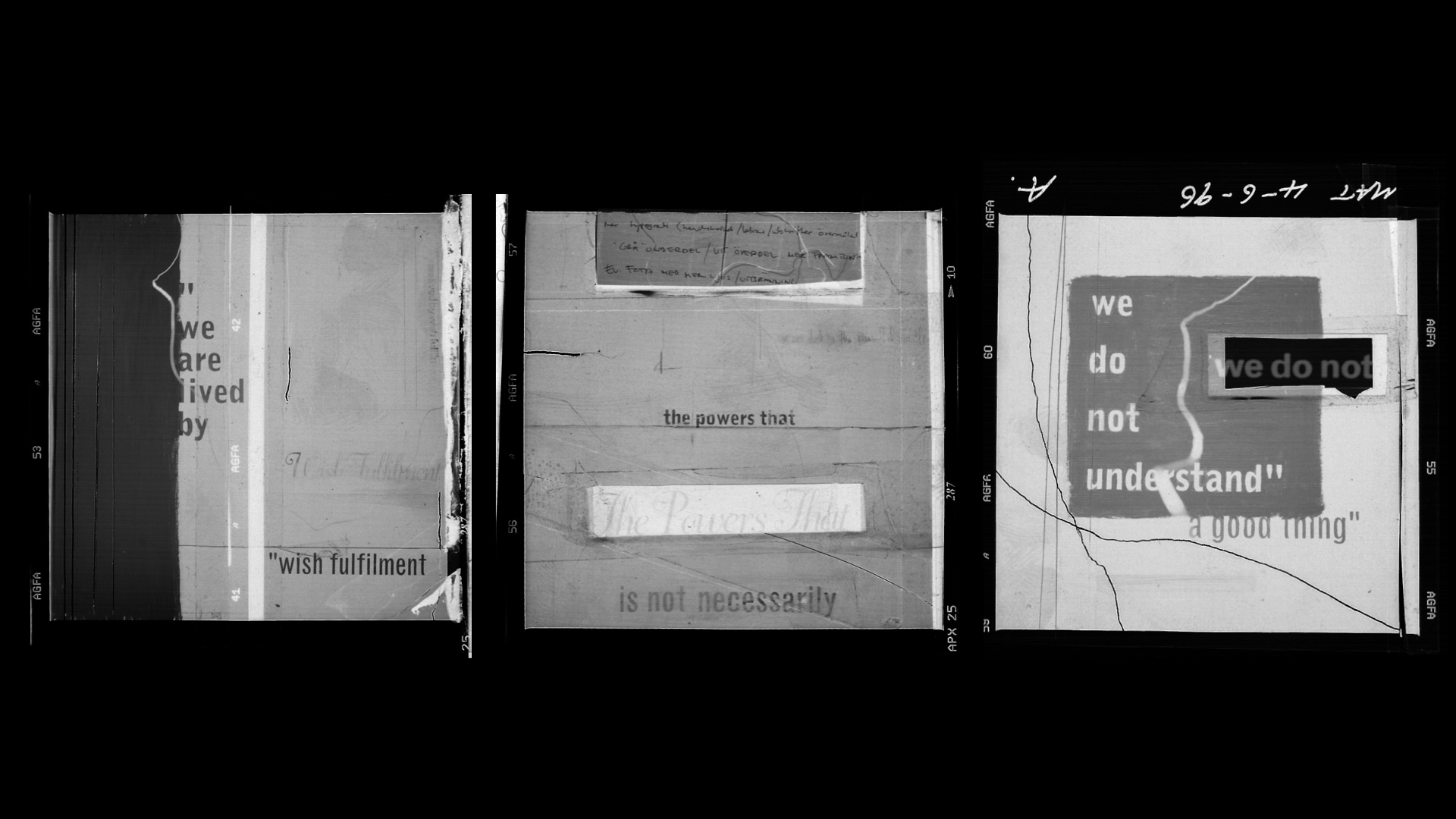

London Art Schools in 1996

In the spring of 1996 I was struggling with my degree show project in graphic design and wanted something meaningful to put on my designated wall-space at Central Saint Martin’s battered old building on Long Acre, London. The lines on my graphic triptych—“We are lived by / the powers that / we do not understand”and “Wish fulfilment / is not necessarily / a good thing”—illustrated my thesis Scene Not Herd, which dealt with the need for subcultures in order to endure contemporary life. Not especially well phrased, but when I reread it today I remember how I was trying to set a compass for the life ahead. I wrestled with anxiety and wrote fragments that, in a visual context, conveyed feelings more than thoughts. Thing is, the tutors kind of dug it.

The most important lesson from my years at London art schools was that they pushed us to find our own voices, our guiding stars for the careers ahead. There were few computers, but plenty of physical space to lay out whatever we wished. This set me on a path where technology only exists to serve art, never the other way around. Which remains the opposite goal of everyone who singles out content as something to “produce” in vast volumes.

After graduating and returning to Stockholm, I tried to build a practice that valued ideas for their artistry and craft rather than hours spent. It was impossible, though: advertising and media were as infected by New Public Management as the rest of the labor market. But bureaucratic audit culture alone wasn’t enough for Swedish agencies and media companies to fully devalue creative work. So they resorted to a tried-and-tested method: separating workers from the finished product. This created the need for an ideological semantic shift. Enter content: everything became a commodity, and the owners of agencies and media houses harvested the profits.

Content became the everyday umbrella term for images, texts, sounds, and films distributed through the internet. Media companies, ad agencies, and new IT firms all listened to Gates’ vision of the internet’s future. And when YouTube, Netflix, Facebook, and Spotify adopted the word, capital’s magic had done its thing. Writers, photographers, filmmakers, and musicians were reduced to “content creators” and lost the authority to set value, which was transferred to economists and engineers—who didn’t value it at all. A single notch in the linguistic hierarchy shifted value from maker to merchant. Big deal indeed.

Today, consumption of pop culture generates higher returns than ever. But just as mushroom growers didn’t get rich from the kombucha boom, creators don’t get a share of it. In short, being a creator in 2025 is not enough to get a mortgage. The creators themselves—often freelancers or micro-entrepreneurs without protection—mounted little or no resistance. Their associations submitted to Big Tech and accepted their new overlords; some even assisted as oligarchs systematically devalued both craft and copyright.

There is, however, an upside. Believe it or not.

When creators are separated from their works, those works lose value, because artistic production—unlike other products—is inseparable from its makers. Authenticity is human; it is what fills works with meaning. Even technically flawless imitations no one will pay for, because it is obvious a computer has merely regurgitated what already exists. Worthless, indeed. Soon it will be impossible to squeeze more money from this separation of creator and creation, and the only thing platforms can offer is volume—anonymous worker ants producing slop. Consumers would rather have access to 200 million than 199 million of whatever, so the desperate chase continues, but only as long as advertisers stay on board. Hence the faint light at the end of the tunnel.

AI is killing the content volume model

Companies are torpedoing themselves by going all-in on a technology that sells containers of commodities no one will pay for in a few years. The internet’s original promise is finally within reach, as even non-technical artists can build their own platforms and reduce Big Tech to what they actually are: advertising channels. It has already begun. Soon established artists from every genre, well-financed production companies, and major visual creators will eat the system from within.

My half-formed images from my 1996 graduation were the beginning of my own origin story: Sweden had just joined the EU and was undergoing deregulations I could sense but that were far too complex for me to grasp at the time. In hindsight, I see clearly that they marked the definitive end of the Folkhemmetera and generated problems our society still lacks the tools to solve. I’m still trying to understand the forces that govern us, and I ask myself daily whether fulfilled wishes really lead to better lives. We never get statistics for the roads not taken—all those risky, thorny side-paths engineers, economists, and politicians need cultural creators to even imagine.

Since 2017, Central Saint Martin’s old building has been an Arket, and culture is traded as a commodity, valued lower than ever. But soon there will be enough fragments to draw a map leading the public to a place where artists have—or once had—beating hearts: a kind of inverted version of Everydays: The First 5000 Days—Mike “Beeple” Winkelmann’s imbecilic NFT that was hailed as a starting point, but in fact was a death sigh.◼

/Mathias