Arrogant Optimism

The solutionist can monetise the present, but any solutions only serving the market’s thirst for novelty is constructing false narratives about the future. Part 2 of the potentially endless series ”Time for Money” is about how white teethed optimists keeps racking up unearned wins.

Technofeudalism as a (weak) Metaphor

The term technofeudalism was popularised by Greece’s socialist finance minister Yanis Varoufakis a few years ago, but was soon criticised for implying that we’ve entered a new era after the end of capitalism. In short, Varoufakis argues that today’s owning class produce nothing of value but instead collect rent on the digital infrastructure we’ve all been made dependent on. The main purpose of new-ish physical products — from iPhones to e-bikes — is to keep us hooked on that digital infrastructure: physical but app-dependent tech for us to update and upgrade rather than maintain. The more dominant a platform is in its market, the larger a share of our harvest the new feudal lords can demand from us peasants.

The idea is potent but weakens when considering old feudal lords’ power was local and bound to sort of protection of workers (often not honoured, but still), while today’s owners are sovereigns with global, state-like power and no responsibilities. And since the few politicians who try to hold the giants to account often seem to do it out of a populist self-interest — being tough on Power plays well with voters — platforms are self-evident targets. This populism produce an absurd yet telling overlap between left and right: in the US, Democrat Elizabeth Warren and Trump apologist Josh Hawley make similar demands of platforms as, for example, ecosocialist Mélenchon and fascist Le Pen do in France. They attack from different angles, and for different ideological reasons, but are all pleased to have a modern Grinch to point to at “the other side.” Enemies matter when you want to be re-elected.

From Land to Networks

The O.G. feudal lords were phased out as larger nation-states and kingdoms where formed, selling off their land to the rising bourgeoisie who had cash to burn; power centralised and the less well-off ended up under the protection of growing tax-funded armies instead of the whims of the lords.

But the biggest digital sovereigns moving freely on the web of global capitalism aren’t feudal lords so much as their gods. Gods with ultra-neoliberal worldview that the lords and lords-in-wating emulate in hope Mammon will reward them even more. The progressive left has no solutions beyond hoping for break-ups of the platforms. The other option — revolution — would require the state to seize the platforms. But which state? Power in both the US and the EU adores the neoliberal project since it generates them so much wealth. They won’t rush any radical change unless voters demand it. And voters are busy making TikToks and cheating with AI.

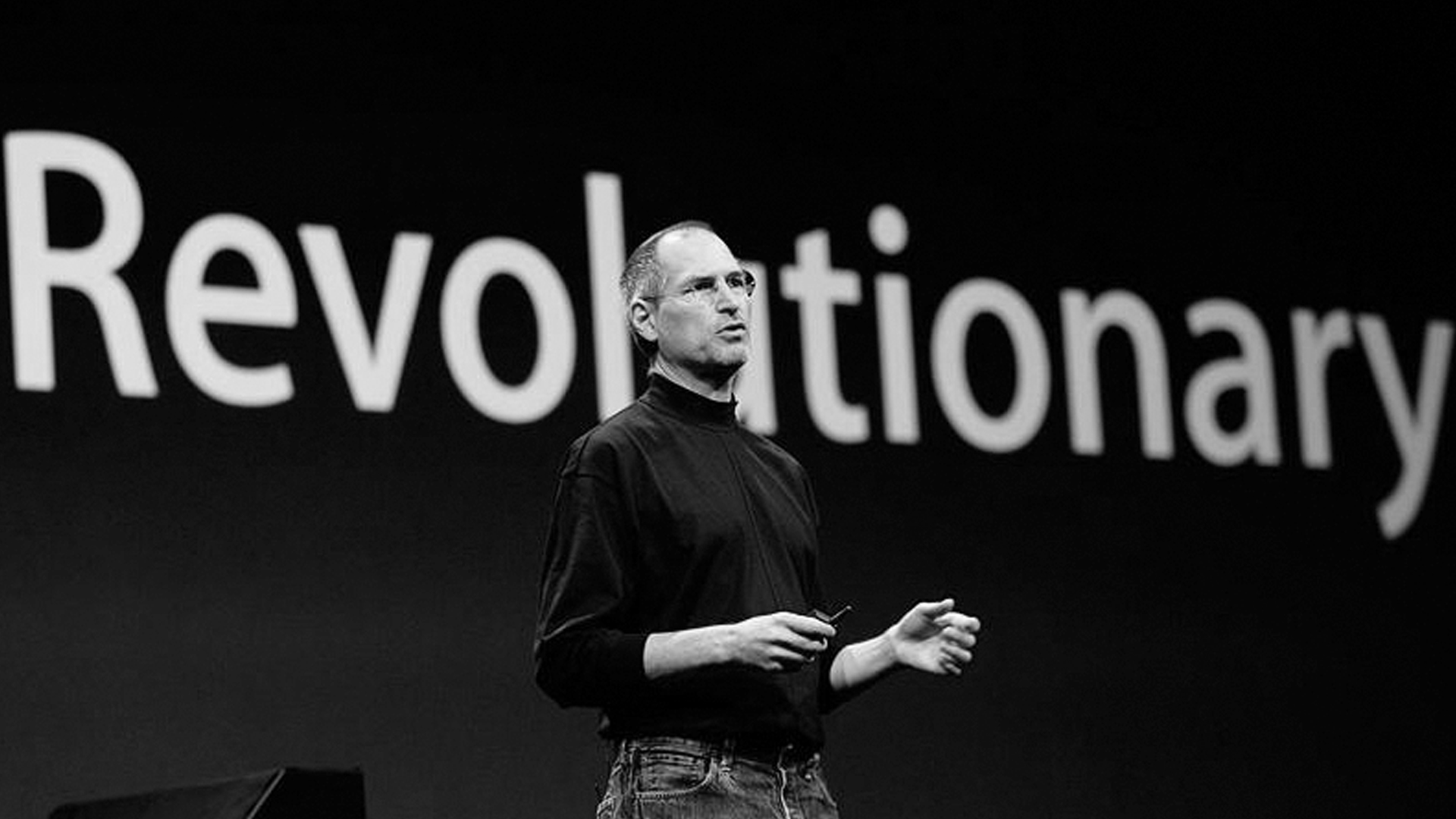

Power Dressed up as Entertainment

Challengers – i.e. fast-growing smaller companies – are either bought up or crushed by Big Tech, whose owners are cosplaying entertainers to obscure the scale of their power. Because power implies responsibility, and responsibility costs money — money shareholders want paid out as dividends. Steve Jobs famously dressed in a black Issey Miyake turtleneck, dad jeans and New Balance sneakers – to achieve his goal: to be viewed as a great humanist and not a mere CEO. “Jesus, Gandhi, ME,” as comedian Bill Burr summed up the tone of Apple’s ads under Jobs. Like many American politicians, he ran out on stage for bloated product launches because it’s so advantageous to be seen as an entertainer in the US. But Jobs wanted to brand himself less as Jesus or Gandhi and more as a Walt Disney of the digital age. This became extra obvious when his side company Pixar became Disney’s largest shareholder.

The reason spells optics: the world sees entertainers as harmless. Variations of kooks, creatives or nerds are easier to stomach than reality. Apple’s pivotal former chief designer Jony Ive doesn’t seem — even in mature age, atop a mountain of money — to have begun reflecting on Silicon Valley’s claim to absolute power over our lives. When he sold his new company LoveFrom to OpenAI for six billion dollars, he instead reminded us that he was drawn to “The Valley” for its optimism, and to create “amazing products that elevate humanity.”

Power is a motherfucker. So they make it a joke.

The world’s consumers would never accept Jobs, Zuck, Musk — or Daniel Ek as we’re zooming in on music — if they hadn’t been elevated to sort of combined entertainers or philosophers. People all over the world has in common that they tend to see artists as a humanist in touch with God. Engineers, programmers, economists and salespeople — not so much. There’s a reason it was so widely reported that Jobs took a calligraphy class once: to keep us from thinking too hard and realising he’s an unelected corporate leader with more power than most heads of state. Hence the routine of the founder of IKEA, Ingvar Kamprad: suppress all extravagant impulses. In our self-aware 2000s, there’s no room for Gianni Agnelli-style peacocks. But sovereigns powers has grown to absurd proportions, and they now gatekeep our access to whatever market we might want to enter.

The New Sovereigns

Our Swedish home-grown Daniel Ek is a hobo in comparison to the other oligarchs, yet the most affluent figure in music-industry history — if we exclude David Geffen, who only has the music business to thank for about 10% of his vast fortune. With wealth on the order of Togo’s GDP and final say over hundreds of thousands of creators’ ability to reach any audience, Ek holds a wildly disproportionate power over the world’s most vital artform. Like the other sovereigns, he and a handful of lieutenants oversees algorithms that can make — or erase — careers. Spotify is his totalitarian state.

We ended up here because we keep voting for politicians who take tech promises as gospel and treat any request for slowing down as a threat to their ability to claim they where “productive” in office. No one votes for a theoretical critic — Varoufakis lasted only six months because he clashed with every finance minister in the Eurozone, telling them the austerity measures they wanted to enforce on Greece where far to harsh. And, like anyone who questions or problematises the finance/tech all-in mentality, he was called a reactionary and a communist. It’s long been obvious that even those steering the top-level systems do so out of self-interest — Greece had to adapt at any cost, and the recovery would then be held up as proof that nothing’s wrong with modern capitalism. Just a little hiccup, apparently.

Ideological Optimism, Creative Destruction

One of arts most important features is to add new perspectives and show alternative paths forward for both lost individuals and broken societies. The problem is that, from business’s current vantage point, society works just fine; there’s no incentive to change or unwind structures. Ask the hundreds of new billionaires Sweden has minted since the millennium — or their spheres of employees, suppliers and social networks. You won’t hear many arguments for altering the world order established across half the West in the 1980s. But NPM and “tech,” in the broadest sense of the word, are really just efficient capital management dressed up as efficiency and innovation. And yet our common ship is steered by those principles, as they’re easy to quantify.

Capital loves the solutionists and shuns the critics, even though both work with problem-formulation — criticism of existing systems and criticism of existing solutions. The solution-oriented say “we renew,” “we replace,” “we tear down to build” — the latter a central feature for this year’s Nobel laureates in economics. But creative destruction only advances humanity when it’s carried by insight into what humans actually need, not when self-interest — hoarding power and/or money — gets dolled up as empathy for consumers.

Cheer Up!

In 2009, Barbara Ehrenreich’s Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America was published. Her experiences in US cancer care led her to see how totally baseless positivity had become an ideological tool to suppress criticism by pinning any problems on the individual rather than burdening the system. And the horror stories from Swedish healthcare whistleblowers suggest we’re heading the same way — when we make that private health-choice the blame becomes ours when things go wrong.

If you end up in trouble, it’s your own fault — “make other choices, get other results,” as Swedish vice prime minister Ebba Busch so very insightfully tweeted in 2014.

Since Reagan and Thatcher inspired the West’s neoliberals to begin starving the state with laser-focused hyper-individualism in the early 1980:s, both the EU and Sweden have lagged a decade “behind” in market-orientation compared to the USA. Today, any opportunist with financialised tech fixes for any and all of culture’s problems now get the kind of political attention they didn’t fifteen years ago.

Remember: as US and UK banks were bailed out with tax money, the Obama years of well-meaning compromise didn’t help at all. The American right came to develop the rabid identity politics that forced huge cuts to public funding and is still ongoing. In Britain, the Tories tried to make people quiet down with quite mild austerity measures.

History repeated itself, as it always does, and Swedish politics are behind the curve, stepping on exactly the same mines as others have before despite all available facts. But maybe all will be fine, it’s not like anything special happened in the UK and the US in 2016.

Since the Swedish right insist on staging the very same plays that already flopped in the US and the UK, perhaps there isn’t much more we can do — beyond noting that in 2026 arts funding should be so low it can be drowned in a bathtub.

Instead of Music: Confusion

In Sweden, having a global-sounding name like Strategic Tech Solutions is often enough to give a company far better odds of public funding than ambitious arts projects with tricky ideas. To keep culture’s role intact in our fragile democracy, I have a proposal. I’m calling it I stället för musik, förvirring (Instead of music, confusion), after the iconic Swedish indie band Bob Hund’s gem. Here’s how we’ll do it now: every artistic project seeking funding registers a company and uses AI to generate a name that at least vaguely reflects the project’s core themes. Then AI writes the pitch based on the name and a couple of project keywords. What it is artistically doesn’t matter — what’s needed is a hazy “tech” business idea with a massive potential Total Addressable Market.

Voilà: culture gets better odds of funding than with any thoughtful accounts of artistic exploration. Now the projects can apply to the business vault holding over 120 billion, instead of relying on the culture cup of roughly 3 billion.

If that isn’t positive solution-orientation, I don’t know what is.◾

References

- Franke – Optimismens hån (album, 2003)

- Yanis Varoufakis – Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism (book, 2023)

- Evgeny Morozov – Critique of Techno-Feudal Reason (essay, 2023)

Vidare läsning:

- Nicholas Vrousalis – Technofeudalism Is Just Capitalism (article)

- Mariana Mazzucato – The Value of Everything (book)

- Geert Lovink – Sad by Design (book)